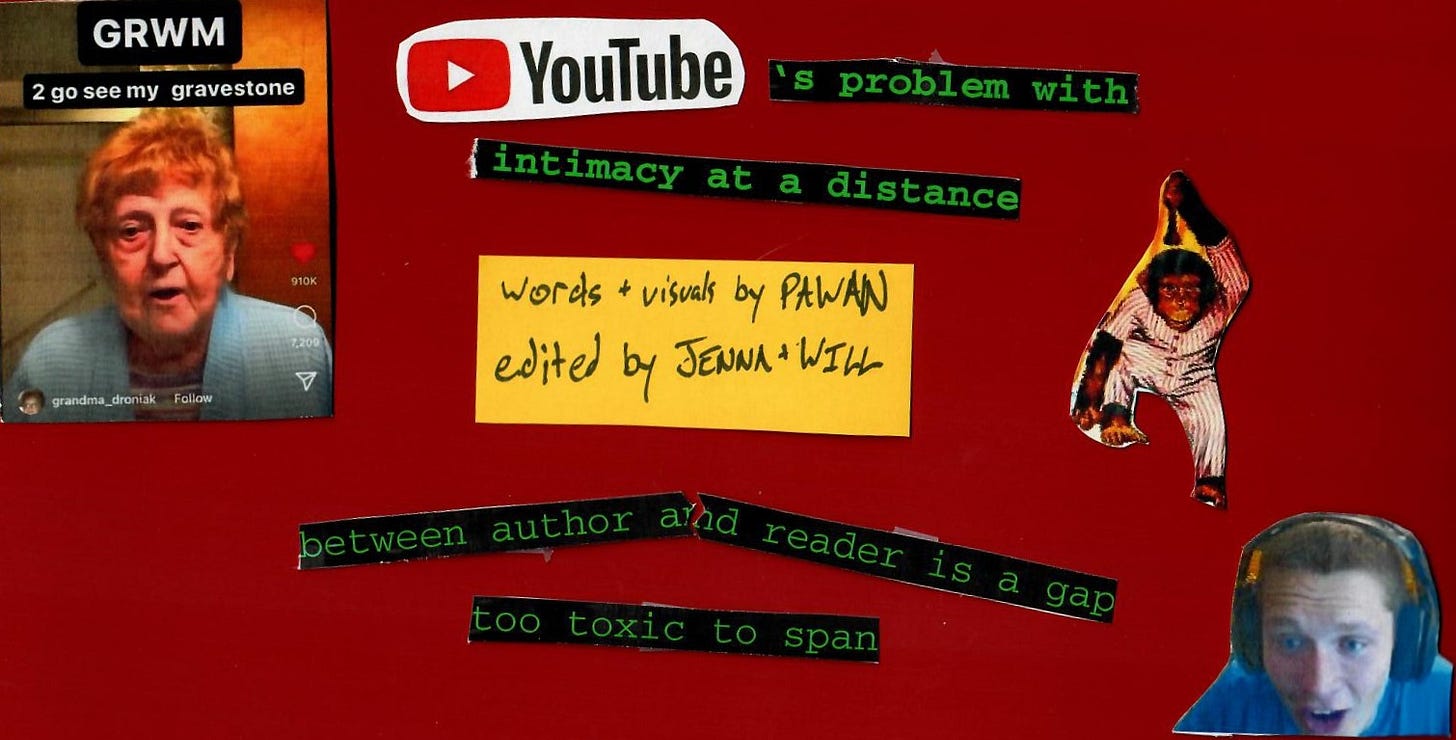

YouTube’s problem with intimacy at a distance

Subscriber != friend... unless?

What’s up my dear friends, it’s Good Faith Wrong Place here with a new post wherein I hawk cheap garbage via my Amazon affiliate link and direct you to this sick horse-betting site I just found(ed)!

The above is a 1:1 facsimile of faking the familiarity between a creator and consumer, so the latter doesn’t know that the former is making a buck. It’s called parasociality and it has taken over YouTube.

Media critic LeadHead has a great video on parasociality targeting children and her own relationship to a sizeable audience. She’s exploring the subject from an authorial view but there’s more than one way to #SponThisCon so in this post, I’ll examine some cinematographic and semantic quirks of online parasociality. Today I’m asking,

Can we still be friends if I ‘Skip Ads’?

Interpellating intimacy

YouTube didn’t invent the parasocial — ask Ronnie Reagan.

‘Parasociality’ was coined in 1956 by Donald Horton and Richard Wohl. Horton, Wohl, and later researchers noticed that as broadcast media spread, emotional attachment to those being ’cast grew immensely, unlike anything observed in the print media age.

The grisly pinnacle of early parasociality is John Hinckley Jr.’s harassment of actress Jodie Foster and his near-murder of four men, including then-President and Bedtime for Bonzo co-star Ronald Reagan. For a while afterward, parasociality remained a niche term with which you could misattribute mental distress as mass media malfeasance. Then we came online.

The early Internet was largely real-world media, replicated. Celebrity coverage saw a renaissance thanks to the morally bereft and digitally connected, to be sure, but blogs like PerezHilton were as trashy as their broadcast bottomfeeder antecedents, adorned with a refresh button. The Internet was waiting for its perfect, parasocial paragon; we were waiting for YouTube.

What is up YouTube

It’s a clarion call for the bored, the wandering, those with a meal to eat and fear of silence.

Hey guys.

Hey Guys is quintessentially YouTube: brief, friendly, simple, and English. The phrase is unique to the web because no television host or stage performer would find it appropriate, fearing its informal, low-rent presentation. It’s perfect for YouTube.

The audience’s first moments are what every artist agonizes over. What swatch of paint first draws the eye? Does the reader like my humorous introduction? A vlogger frets over the same and they’ll let Hey Guys stand in because despite its ubiquity, it’s still uniquely YouTube.

As an aside, many hallmarks of vlogging are inherited from blogging, but plenty more were left on the .txt file when we jumped to .mp4. The vlog, as a medium, doesn’t use hyperlinks with the same frequency as the blog medium because, technologically, blogs were incentivized by search engines rewarding ‘backlinks.’ Vlogs having developed in an algorithmic, tags-based economy of search means they’re less concerned with that.

When we hear Hey Guys, we’re treated to a new linguistic context, one of casual familiarity which is foreign to traditional media. YouTubers have not stopped there, either, because shaving down the creator-viewer barrier makes for good business.

I’ve covered the concept of predatory community before but suffice to say, creators want your attention and are willing to falsify familiarity to get it. This can happen inadvertently, of course, but when PewDiePie, one of the platform’s all-time heavyweights, dubs his fanbase his “bros,” it’s difficult to deny parasociality’s efficiency.

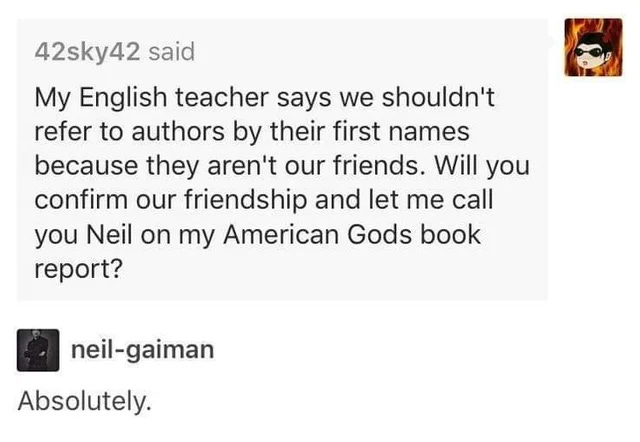

The semantic signs of parasociality are subtle. Using plural pronouns like ‘we’ over ‘I’; liberal reference to audience interaction tools like polls, comments, messages, etc; employing more ‘authentic’ language such as expletives, rambling, mispronunciations, or anything else that doesn’t serve the express narrative and one would expect to be cut from a final product. When these moments make it in a commercial product, it’s because they serve to elicit intimacy and chime a conversational tone belying the author’s complete control.

The pursuit of parasociality can also be much more overt, as we see in the Get Ready With Me genre. This is a diverse niche replete with fun permutations but the core is a person, usually a conventionally attractive young woman, sits down and does her makeup, hair, and gets dressed to go out. All the while she monologues about an event in her life or her perspective on the world, regularly checking in with the viewer via reflexive comments, like “I hope this looks good,” or questions to the viewer, “Have you ever had that happen?” or simply “you know?,” rhetorical in every sense of the word.

The GRWM community, as it’s known, forms the bleeding edge of parasociality on YouTube. The biggest members also prove ruthlessly commercial, acting as conduits for some of the world’s largest corporations to look you in the eye and call you ‘bestie.’ Where it used to be Herbalife or Avon MLMing their way to you through loved ones, Nyx and L’Oréal just leverage the YouTubers who you pretend are your friends.

Not to leave this as gendered, particularly with GRWMs being genuinely fascinating content, the more ‘masculine’ side of YouTube has a far funnier, grimmer headline: Gamers lie to kids about gambling. We’re still measuring the effects of gambling advertisements on content children love but suffice to say, gamers and GRWMers profit off of an often-unwitting audience by pretending to be a friend.

Including insidious, excluding earnest

I can’t do the topic of parasociality on the Internet justice.

What this post doesn’t talk about is whether Horton and Wohl had stumbled onto the new metric for social cohesion in the Internet age, and if their idea of parasociality maps uncomfortably well onto the instant messenger/Zoom call friendships so many of us dearly cherish. It’s too much to say that online relationships are inherently false, but how do we delineate between online friendships and parasocial interaction?

Put differently, what definitionally is the difference between a GRWM girly calling you their friend and you heart-reacting a buddy’s message — or do we just know it when we see it? What are we losing if we decide that between author and reader is a gap too toxic to span? How wide is the cyberspace between you and your loved ones?

These questions aren’t exclusive to the Internet but are core to understanding our relationship with the media we consume and the folks who create it, which is why I advise critical thinking even when it’s just a YouTube video.

Every creator has an incentive to make you believe them.

Trust me.

Edited by Jenna and Will.